I just received a completely unsolicited email from a 66-year-old quilter who purchased Target Tendonitis a few days ago:

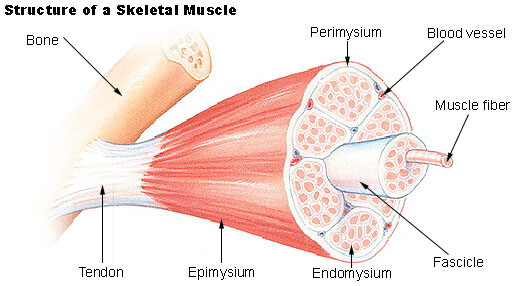

Alex – I purchased your ebook yesterday and viewed the videos today and am excited to begin the exercises tomorrow. Your explanations re bicep tendons were so helpful. Your reference to pronation and supination absolutely explained to me why my pain is so much worse after doing simple things like knitting/quilting. But I now realize the motions used are exactly what you describe and could explain the bicep tendon pain I suffer after doing these activities. Also I kept thinking my pain occurred on extension and not flexion, but after your explanation I can see that actually the pain is occurring with pronation of my arm.

Thank you ever so much for the information not only in your book but the videos – doubt if I could have understood the exercises and gotten the above explanation just from the book. After recently becoming very discouraged with the issues I’ve been dealing with for 6 months and trying most of the therapies you described [as being ineffective], your videos have given me hope that maybe this condition/issue WILL get better and possibly go away.

thank you!

Take Care, Jean

First, I’d just like to say that it makes me very happy to receive this kind of feedback about the new TT video. Makes all the effort of putting it together worth it. So thank you, Jean!

Second, as a general comment I think that as we age it becomes more and more important to manage recovery in an effective manner. It just takes longer to reap the gains that comes from an increase in exercise intensity, or duration, or frequency, etc. In a subsequent email Jean said that she found that upping her yardage in swimming was the immediate precursor to her injury, which frankly doesn’t surprise me. I see this sort of thing over and over again in my business. And I personally spent the first part of my 40s trying to convince myself that I was still in the middle part of my 30s, hahaha.

If you are a regular exerciser, or if you perform any sort of motion on a repetitive basis, it makes sense to take a step back every few years and re-evaluate just how long it really takes to recover from a session. If you’re in the gym, be sure to keep a good workout log that includes the time between maximal weight attempts. (If you’re not getting stronger, the culprit is very likely insufficient time between such attempts.) And if you’re a knitter or quilter, like Jean, try cutting back about ten percent per decade after the age of 50. Doing so will still allow you to enjoy your hobby, but will go a long way toward keeping tendon issues from becoming a chronic problem.